- 57 minutes ago

- 14 min read

Wealthy Switzerland’s European role at risk if voters approve a population cap

Strong opposition to population cap from Swiss business and the country’s all-important international community. Other European right-wing parties may want to follow the Swiss example

By The Immigrant Times

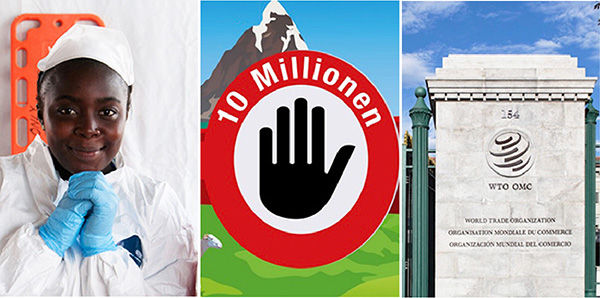

If Swiss voters approve a population cap, the country’s health sector will face staff shortages. Meanwhile, international organisations, like the WTO, based in Geneva, will rethink their presence in Switzerland.

The ‘No to a Switzerland of 10 million’ referendum

February 2026: On 14 June 2026, Switzerland will head to the polls to decide whether to cap the country's population at 10 million people, a threshold that, if approved, could fundamentally reshape the nation's relationship with immigration, the European Union, and its own identity as one of Europe's most prosperous and internationally connected economies.

The referendum, officially titled ‘No to a Switzerland of ten Million’, (Keine 10 Millionen Schweiz) is the latest initiative from the right-wing Swiss People's Party (SVP), the country's largest political party and a driving force behind anti-immigration politics for more than three decades. With Switzerland's current population at 9.1 million and growing, the proposal would require the government to begin restricting asylum admissions and family reunification for foreign residents once the population reaches 9.5 million. If the 10 million mark is crossed, authorities would be compelled to terminate Switzerland's free movement agreement with the European Union, its largest trading partner.

The vote represents more than a policy decision; it is a test of Switzerland's direct democracy. This uniquely Swiss system, rooted in centuries of local governance traditions and formalised in the 19th century, allows citizens to challenge laws and propose constitutional amendments through referendums, a practice that occurs with remarkable frequency. Swiss voters typically go to the polls four times a year on issues ranging from pension reforms and climate targets to tax policy and healthcare funding. In 2024 alone, citizens voted on everything from a 13th month of pension payments to biodiversity conservation and motorway expansions. Just this past February, they rejected an "environmental responsibility" initiative that would have imposed sweeping limits on economic activity.

But referendums on immigration have become a signature issue for the SVP, which has made restricting foreign arrivals central to its political platform since the 1990s. The party successfully pushed through a 2009 ban on the construction of new minarets and narrowly won a 2014 referendum "against mass immigration" that aimed to reintroduce quotas on EU citizens—though subsequent negotiations with Brussels significantly watered down its implementation. More recently, voters rejected SVP-sponsored initiatives in 2016 to automatically deport immigrants convicted of minor crimes and in 2020 to end free movement with the EU entirely.

Yet polling suggests the population cap may prove different. Recent surveys show 48 per cent of voters support the measure, compared to 41 per cent opposed, a notable margin that has alarmed opponents across the political spectrum. Both chambers of parliament, the Federal Council, and major business groups have strongly opposed the initiative, warning that it could trigger labour shortages, damage key industries, and unravel Switzerland's carefully negotiated bilateral agreements with the EU. But with the SVP having become the largest party in Swiss politics by championing such issues, and with popular anxieties about housing costs, infrastructure strain, and wages running high, the outcome is far from certain.

For Switzerland's immigrant communities, who make up roughly 27 per cent of the population and include everyone from Italian construction workers to German bankers, Portuguese cleaners to French researchers—the stakes are deeply personal. For the European Union, which concluded a new bilateral agreement with Switzerland in 2025, the referendum represents a potential diplomatic crisis that could upend decades of carefully cultivated cooperation.

A wealthy Switzerland relies on foreign labour

Switzerland has one of the highest per-capita immigration rates in the developed world, a reality that often surprises those who view the Alpine nation as insular or conservative. With roughly 9.1 million residents, approximately 27 per cent hold foreign nationality, while 40 per cent of the total population has a migrant background. These figures place Switzerland alongside Australia and Canada as countries with the largest proportions of foreign-born residents, and well above most European nations. In absolute terms, this means more than 2.4 million people living in Switzerland were born elsewhere.

The growth has been dramatic. Switzerland's population has increased by roughly 25 per cent since 2000, reaching 9.1 million from just over seven million, a pace approximately five times faster than neighbouring EU countries. In 2024 alone, Switzerland received 136,000 new permanent or long-term immigrants, a 6.2 per cent decrease from the previous year. Of these arrivals, 74 per cent came through free movement agreements with the EU, 15 per cent through family reunification, 10 per cent as humanitarian migrants, and two per cent as traditional labour migrants subject to quotas.

In 2024, Germany, France, and Italy were the top three nationalities among new arrivals. Portugal registered the strongest increase with 3,100 additional immigrants compared to the previous year, while Croatia saw the largest decrease at 600—likely reflecting that country's improving economic conditions.

Switzerland's dependence on foreign labour spans nearly every sector of its economy, from the most prestigious to the most humble. The country faces critical shortages across multiple industries, with employers seeking to fill over 250,000 vacancies in 2024 alone. By 2040, industry associations estimate Switzerland will face a labour shortage of 430,000 people.

Healthcare stands at the forefront of this demand. Hospitals, clinics, and care facilities desperately need doctors, nurses, therapists, and healthcare specialists. In 2024, employers posted 2,625 job advertisements specifically for healthcare specialists. Many Swiss hospitals would struggle to function without foreign-trained doctors and nurses, particularly from Germany, France, and Eastern Europe. The Covid pandemic only intensified these shortages, as healthcare workers experienced burnout and early retirement.

The information technology sector, centred in Zurich and increasingly in Geneva and Lausanne, has become another major employer of immigrants. Software developers, data scientists, cybersecurity experts, cloud architects, and AI specialists are in constant demand. Switzerland's tech salaries rival those in Silicon Valley, and English proficiency is often sufficient, making the sector particularly attractive to international talent from India, Eastern Europe, and beyond. In 2024, IT specialists topped the list of most-advertised positions.

Switzerland's construction industry, which has driven much of the country's physical development, relies heavily on immigrant labour. The sector needs skilled workers, project managers, site supervisors, and labourers, positions that attract workers from Portugal, the Balkans, and, increasingly, Eastern Europe. With approximately 39,000 new housing units expected in 2026 alone, the construction sector faces ongoing labour shortages.

The hospitality and tourism industry, a cornerstone of the Swiss economy, particularly in mountain regions, depends almost entirely on foreign workers. Hotels, restaurants, ski resorts, and tourist facilities employ multilingual staff from across Europe and beyond. Chefs, hotel staff, restaurant servers, and ski instructors, especially English-speaking ones, find ready employment. Seasonal work in Alpine resorts has long served as an entry point for young Europeans seeking Swiss experience.

Finance and insurance, particularly in Zurich and Geneva, attract highly educated professionals from around the world. Wealth managers, risk analysts, actuaries, compliance officers, and investment bankers command some of Switzerland's highest salaries. These positions often require specialised knowledge and language skills, drawing talent primarily from other European financial centres and increasingly from Asia.

Manufacturing and engineering sectors, which have built Switzerland's reputation for precision and quality, continue to require mechanical, electrical, and civil engineers, technicians, and machine operators. The watchmaking industry in the Jura region, pharmaceutical giants like Roche and Novartis in Basel, and the machinery sector all depend on both Swiss-trained and foreign engineers.

Even Switzerland's universities and research institutions rely significantly on international talent. ETH Zurich, EPFL Lausanne, and other institutions employ researchers, professors, and postdoctoral fellows from around the globe, particularly in STEM fields where Switzerland competes internationally for talent.

How the population cap would work

The referendum asks Swiss voters to amend the constitution on a deceptively simple premise: Switzerland's permanent resident population, including Swiss citizens and foreign nationals with residency permits, must not exceed 10 million by 2050. But beneath this headline figure lies a more complex mechanism designed to trigger government action well before that threshold is reached.

Two critical thresholds

The initiative operates through two distinct trigger points, each requiring progressively more severe measures:

At 9.5 million (the ‘action threshold’): If Switzerland's population exceeds 9.5 million at any point before 2050, the Federal Council (the Swiss government) and Federal Assembly (the Swiss parliament) would be constitutionally obligated to implement immediate measures to halt further growth. These would specifically target asylum admissions, family reunification policies, and the issuance of new residency permits. According to the proposal, temporarily admitted persons, a category that includes many asylum seekers whose applications are still being processed, would be barred from obtaining residence or settlement permits, Swiss citizenship, or any other right to permanent residence.

The government would also be required to ‘seek to renegotiate international agreements that drive population growth’. This deliberately vague language covers Switzerland's bilateral agreements with the European Union, particularly the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons, but it does not mandate their termination at this stage.

At 10 million (the hard cap): If the population reaches or exceeds 10 million, the initiative requires authorities to deploy ‘all available measures’ to reduce it below the cap. This is where the proposal's most dramatic provision comes into play: if other measures prove insufficient, Switzerland would be constitutionally required to terminate its free movement agreement with the EU. There is no flexibility, no discretion, no room for negotiation. The text is absolute.

The post-2050 adjustment mechanism

Assuming the cap is maintained through 2050, the proposal includes a clause allowing the Federal Council to adjust the 10 million limit annually ‘in line with natural growth’, meaning births minus deaths among the existing population. This mechanism acknowledges demographic reality: a stable population of 10 million Swiss citizens would naturally grow through births, and the initiative doesn't seek to prevent Swiss families from having children. But it effectively means that any natural population increase would further tighten the space available for new immigration.

If, for example, Switzerland had a natural population increase of 20,000 people in 2051, the cap for that year might be raised to 10.02 million—but every one of those additional slots would be absorbed by natural growth, leaving no room for new foreign arrivals.

What the initiative does not specify

Notably absent from the text is any detailed mechanism for how authorities would reduce the population once it exceeds 10 million. The constitution would mandate the outcome but leave the methods to parliament. This ambiguity is both strategic and problematic.

Would Switzerland deny work permit renewals to long-term residents? Force people to leave when their permits expire? Prioritise deportation of certain nationalities over others? The initiative provides no answers. Critics argue this vagueness is deliberate—it allows the SVP to campaign on an appealing headline while avoiding the ugly specifics of enforcement. Supporters counter that such details are properly left to elected representatives to determine through legislation.

The proposal also doesn't establish a quota system or differentiate between types of immigrants. A neurosurgeon from Germany and a seasonal hotel worker from Portugal would be subject to the same cap. A researcher at the University of Geneva and an asylum seeker from Syria would count equally against the 10 million ceiling.

The SVP’s justification of the proposed cap

The Swiss People’s Party (SVP) has marketed the initiative under the slogan ‘preserving what we love’ (Erhalten, was uns lieb ist in German). The official justification cites environmental protection, the preservation of natural resources, sustainable infrastructure development, and the safeguarding of Switzerland's social security systems as primary goals. It frames population growth not as an economic issue but as an existential question about Switzerland's quality of life, its Alpine landscapes, its small-scale governance, and its social cohesion. "Switzerland is too small for 10 million people," the SVP argues in its campaign materials. "We're reaching our limits. Enough is enough."

Strong domestic opposition to the population cap

The remarkable aspect of the population cap referendum is not the SVP's support—that was expected—but the breadth and intensity of opposition from nearly every other quarter of Swiss society.

Parliament rejects the SVP’s population cap

Both chambers of Switzerland's parliament, the Federal Assembly, have formally recommended that voters reject the initiative. The Federal Council, the seven-member executive branch that includes two SVP members, has also come out strongly against it, warning it would ‘endanger economic growth as well as derail key treaties’. No counterproposal was advanced, a signal that the governing coalition sees no middle ground worth offering.

This rare unanimity across Switzerland's usually fractious political spectrum reflects genuine alarm. The Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, Greens, and Liberals—parties that agree on little else—have all pledged to campaign against the measure. "There have been some anti-immigration initiatives before but we have never seen such an extreme fixed-cap proposal before," noted Rudolf Minsch, chief economist at Economiesuisse.

Business is alarmed

The most vocal and organised opposition comes from Switzerland's business sector, which sees the population cap as an existential threat to the country's economic model.

Economiesuisse, Switzerland's leading business federation, has labelled the proposal a ‘chaos initiative’ and pledged CHF 5 million to an awareness campaign. The organisation's research paper warns that EU and EFTA workers contribute disproportionately to Switzerland's pension system compared with the benefits they receive, which means fewer immigrants would strain social insurance finances as the population ages. "The initiative creates new risks for our standard of living," Economiesuisse argues, urging targeted policies on housing, asylum, and infrastructure instead of ‘rigid ceilings’.

The Swiss Bankers Association has joined the chorus, warning that the proposal would jeopardise more than 120 bilateral accords giving Swiss exporters preferential access to the EU single market. Switzerland's multinational giants, Nestlé, Novartis, Roche, and UBS, depend utterly on their ability to recruit EU engineers, researchers, nurses, and managers. Roche alone employs staff from more than 120 nationalities in Switzerland. These companies warn that they would be forced to shift high-value functions abroad if recruitment pipelines are severed.

"This proposal threatens our ability to fill critical positions and maintain Switzerland's competitive edge," a representative from Economiesuisse told reporters. "We're already facing demographic challenges with an aging population, and this would exacerbate those pressures dramatically."

Healthcare warns of staffing crisis

The implications for Swiss healthcare are particularly stark. Currently, close to 28 per cent of workers in the sector are non-Swiss, a proportion that rises even higher in specialised areas and urban hospitals. With 38.4 per cent of doctors having qualified outside Switzerland (as of 2021) and many nurses trained abroad, the sector's dependence on immigration is structural, not temporary.

Swiss hospitals have been posting thousands of vacancies for doctors, nurses, and healthcare specialists. The ageing population means demand for healthcare services will only intensify. Switzerland projects needing to fill 430,000 positions across all sectors by 2040, with healthcare among the most critical. A population cap that restricts immigration to 9.5 million could arrive within five years, precisely when demographic pressures are mounting.

Hospital administrators have been notably quiet in public debate—healthcare institutions in Switzerland are largely cantonal and municipal operations, and they are cautious about direct political engagement. But behind closed doors, planning has begun for what one health system manager called "the unthinkable scenario." Some hospitals are considering dual-contract models or partnerships with facilities in neighbouring France and Germany to maintain access to medical professionals.

Construction would stutter to a halt

Perhaps the most acute immediate impact would hit construction, where 43 per cent of workers are non-Swiss. The sector is already struggling to meet demand. Switzerland expects 39,000 new housing units in 2026 alone, part of an urgent push to address the very housing shortages the SVP cites as justification for the cap.

Critics note that the circularity is clear: Switzerland needs to build housing to accommodate population growth, but restricting population growth would eliminate the workers needed to build it. Swiss construction firms depend on Portuguese, Balkan, and Eastern European labour for everything from specialised trades to general labour. Replacing them with Swiss workers is not feasible at current wage rates and training timelines.

Geneva's international role at risk

Tucked between the Alps and the Jura, Geneva punches far above its weight on the global stage. The canton hosts 38 international organisations, 24 of which have headquarters agreements with Switzerland. These include the European headquarters of the United Nations, the World Health Organisation, the World Trade Organisation, the International Labour Organisation, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and hundreds of NGOs (Non-governmental organisations).

Together, these institutions employ approximately 28,730 people directly, with an additional 4,025 working for countries' permanent missions to the UN and other international organisations. NGOs add another 3,276 employees. In total, "International Geneva" represents roughly 36,000 jobs in a canton of 500,000 people.

Nearly all of these positions are held by foreign nationals. Geneva's population is 41.3 per cent non-Swiss, with 72 per cent of foreign residents coming from Europe. The city functions as a truly international hub, where diplomats, researchers, technical specialists, and aid workers rotate through on assignments that typically last a few years before they move onward.

A population cap would fundamentally undermine this ecosystem. International organisations cannot function if their staff—often recruited globally for specific expertise—cannot obtain Swiss residency. Would a WHO epidemiologist responding to a pandemic outbreak count against the cap? Would a WTO trade negotiator? Would their families?

Yet this angle has received surprisingly little attention in public debate. The SVP's framing focuses on housing and infrastructure strain, not Geneva's international architecture. When pressed, SVP representatives suggest exemptions could be negotiated for international staff, but the initiative's constitutional text contains no such carve-outs, and legal experts warn that creating categories of ‘cap-exempt’ foreigners would violate Swiss principles of equal treatment.

The relationship with Europe at stake

For the European Union, Switzerland's population referendum represents more than a diplomatic irritant, it threatens to unravel one of the bloc's most intricate and hard-won relationships.

Just last year, after years of arduous negotiations, Switzerland and the EU concluded a carefully balanced agreement to preserve and improve Switzerland's access to the single market. The deal updated dozens of bilateral accords, streamlined regulatory cooperation, and resolved longstanding disputes over state aid and workers' rights. Swiss President Guy Parmelin and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stood together in Davos to announce what both sides called a historic breakthrough.

The population cap referendum puts everything at risk. If Switzerland's population reaches 10 million and the initiative requires terminating the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons, EU officials have made clear what would follow: under the ‘guillotine clause' embedded in Switzerland's bilateral treaties, ending one major agreement terminates them all. Switzerland would lose access to the single market for goods, services, research collaboration, and much more.

The EU is Switzerland's largest trading partner, absorbing more than 40 per cent of Swiss exports and supplying about 70 per cent of imports. Swiss companies have built supply chains, research partnerships, and commercial relationships, assuming barrier-free access to 450 million European consumers. That access would evaporate.

A European domino effect?

Beyond Switzerland's borders, far-right parties across Europe are watching the June referendum with keen interest. If Swiss voters approve a fixed population cap, it would provide a powerful template for anti-immigration movements from Vienna to Amsterdam, from Stockholm to Rome.

Germany's far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), now polling at record levels, has already begun discussing ‘remigration’ policies that would reverse immigration. Some party members have openly speculated about " a Germany of 70 million’, a reduction of 14 million people from the current population of 84 million. Marine Le Pen's National Rally in France, Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, and Italy's governing coalition all frame immigration as an existential threat to national identity. A Swiss success would equip them with a concrete policy model and the democratic legitimacy of a referendum victory in one of Europe's wealthiest and most stable nations.

The precedent would be particularly potent because it comes from Switzerland, not a populist outlier but a country synonymous with pragmatism, prosperity, and careful governance. If even the Swiss conclude that 10 million people is too many, the argument would go, how can larger, poorer, more troubled nations justify their current levels?

For opponents of the cap, this makes the stakes on June 14 far larger than Swiss housing costs or Alpine infrastructure. They're fighting not just for Switzerland's economic model or its relationship with Brussels, but against a potential watershed moment in European politics—one that could shift the entire continent's conversation about immigration from "how do we integrate newcomers?" to "how do we stop them coming?"

The SVP has spent three decades perfecting the populist playbook. Now, Europe will discover whether that playbook works even when arrayed against unified opposition from government, business, healthcare, and international institutions. The answer Swiss voters give in June may echo across the continent for years to come.

Further reading from The Immigrant Times: Switzerland is Europe's role model for integrating immigrants ||

COMMENTS

FOLLOW